Back in Five Minutes

Production : Sebastian Verdon

Back in Five Minutes, 2022

Matériaux divers, aspirateurs robots, gélatines.

Les photos rendent compte des variations de l'ambiance colorée (allant du rose pâle au violet intense) en fonction de la lumière de jour provenant de la verrière du centre d'art.

A daring new business venture seems stalled in its tracks.

Or is it a social event for lonely low-level employees?

The receptionist has apparently just stepped out and should return shortly, long enough in any case for other entrepreneurial maggots to take root with their own pop-up stores.

But, they’ve gone missing as well.

All that’s left are the machines executing their moves in the rink-cum-playpen-cum-stockyard…and a few humans to watch.

Will their owners return or have they been abandoned? The blissful indifference makes it anyone’s guess.

I’m off to the lake to ponder the ducks.

Crédit photo: Sebastian Verdon

Photos : Francesco Finizio

Photos : Bénédicte Le Pimpec et Maxime Bondu

The only thing that seems to work in a manner closest to perfect in this world, is online shopping. Everything else just does not work! One could simply observe the incompetent rollout of the COVID vaccine, while online orders were running smoothly. The digital concretizes the abstraction of finance back into our experience of the world. With financialisation, the locus of activity moved from labour to debt, the social realities of digital technologies did not resolve alienation but folded it into a totalising metabolic synchronisation; The political meaning of this eradication of the social morphed any notion of revolution into mere disruption; under these conditions, the exploration of the possible, which was meaning-oriented, has transformed into a pattern augmentation of the probable, and the aesthetic application of these realities switched any notion of a cultural avant-garde to a mere speculation within the parameters of capitalist perpetuation. In this sense, this is the worst of all possible worlds for the simple reason that it cannot imagine other worlds.

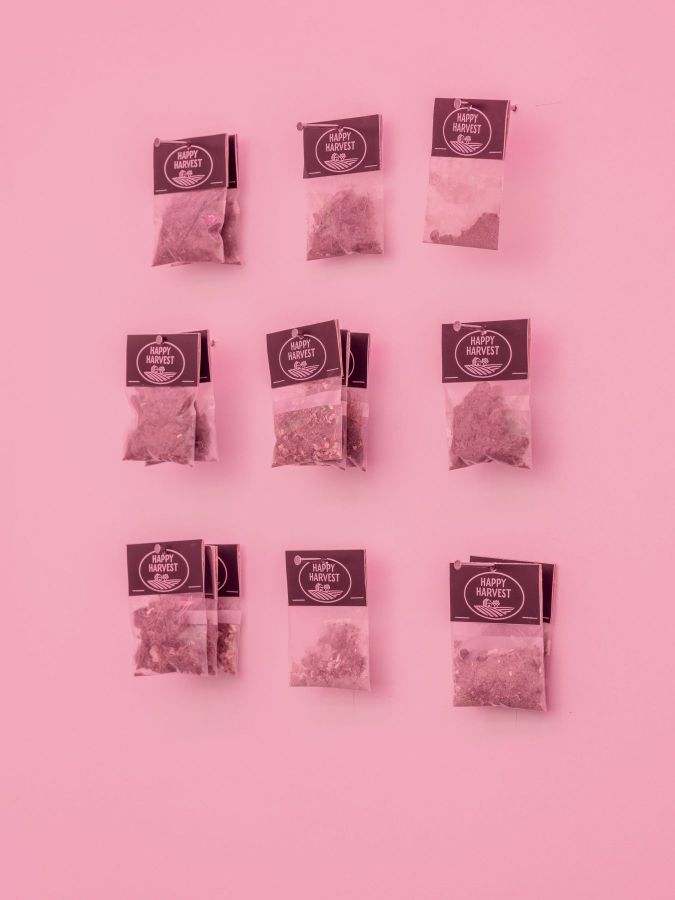

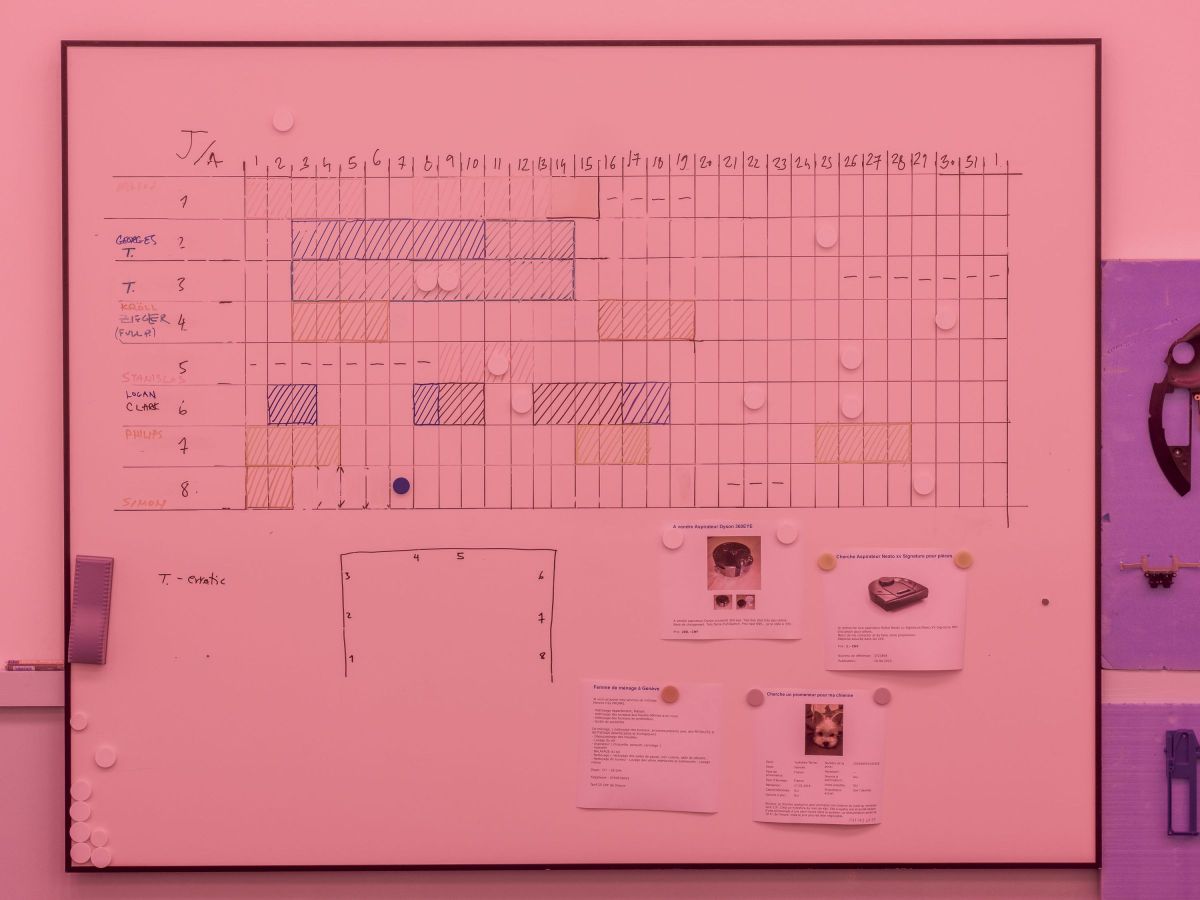

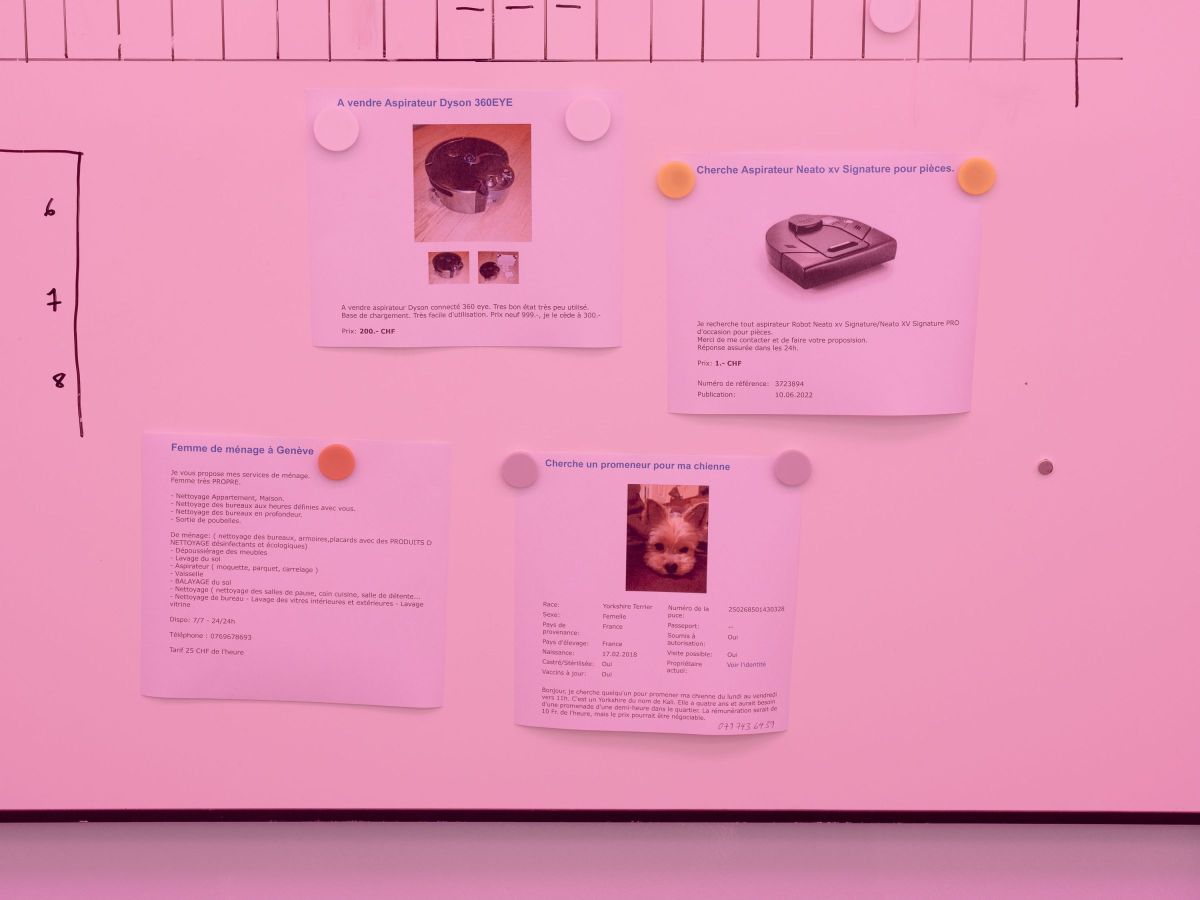

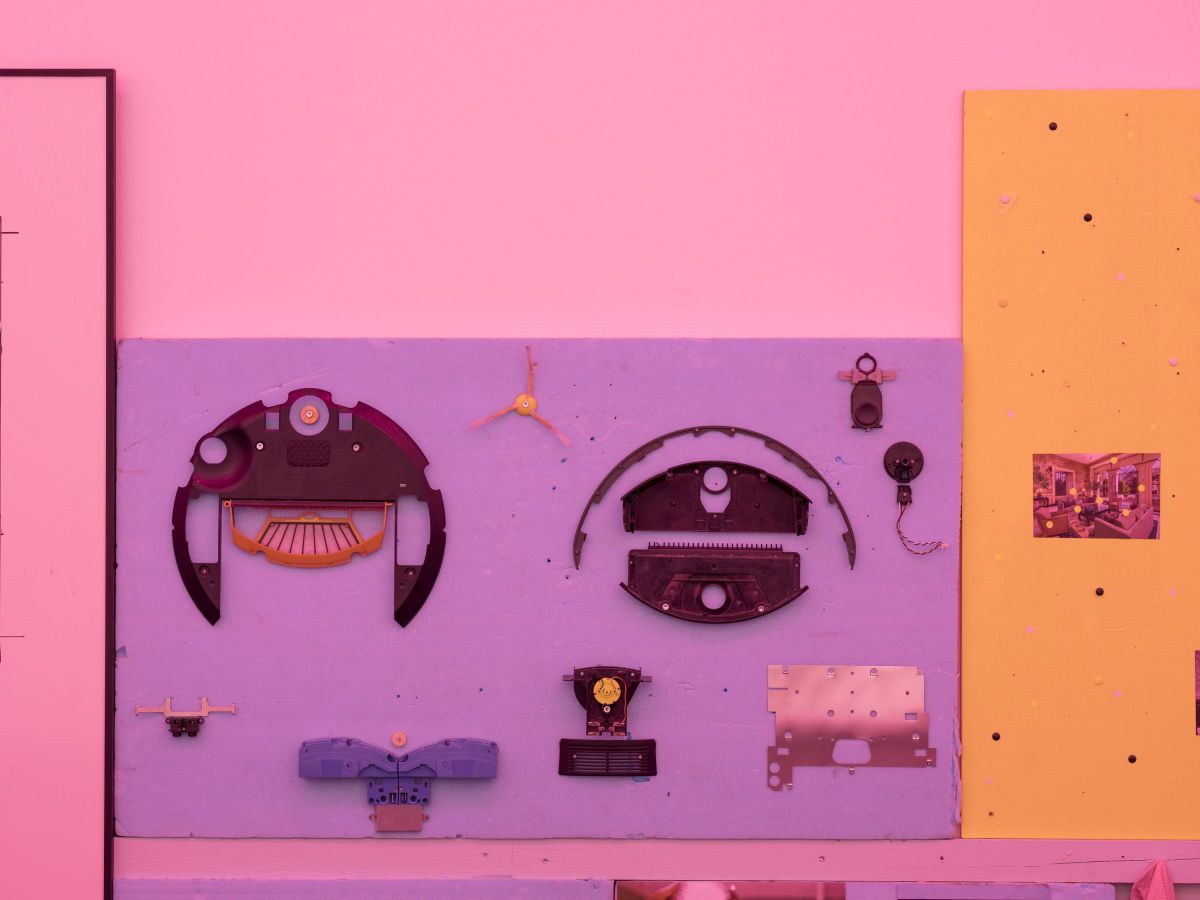

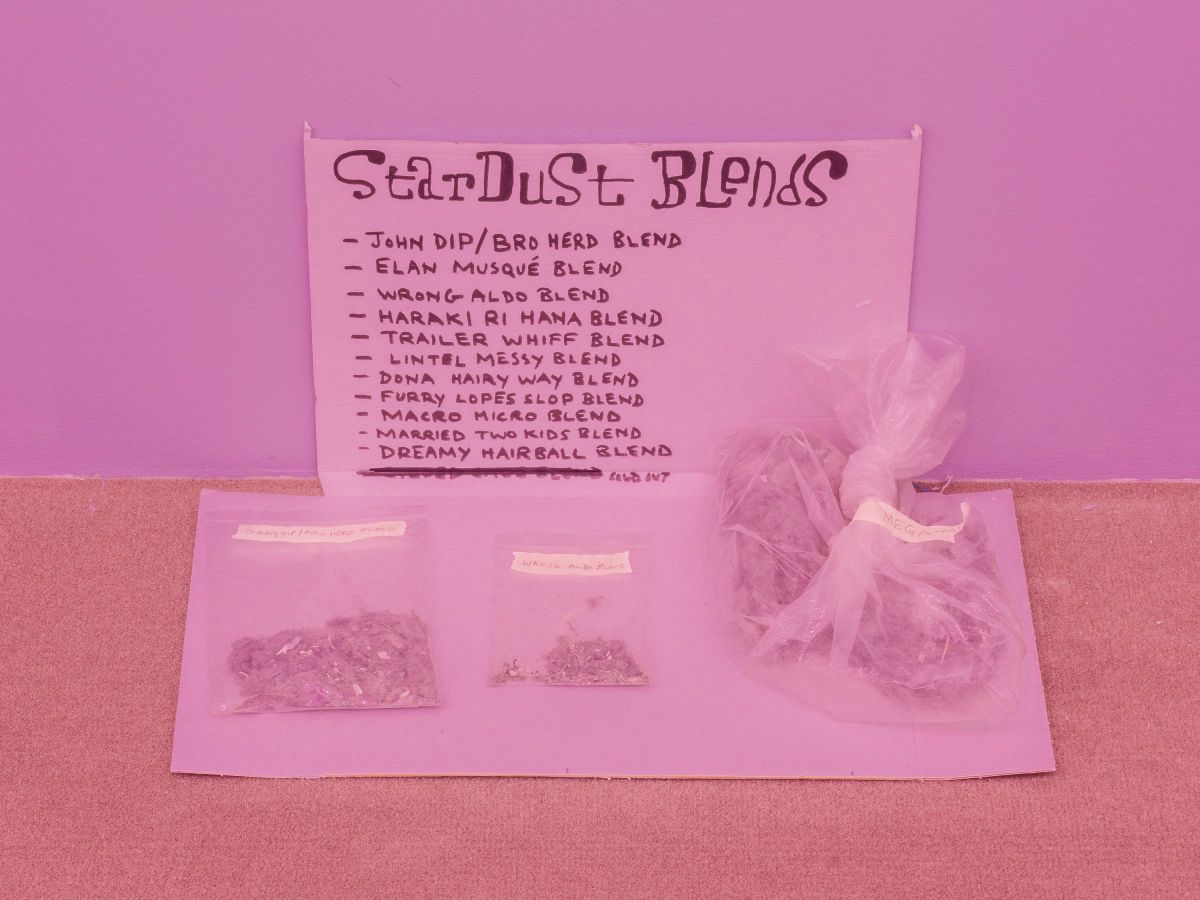

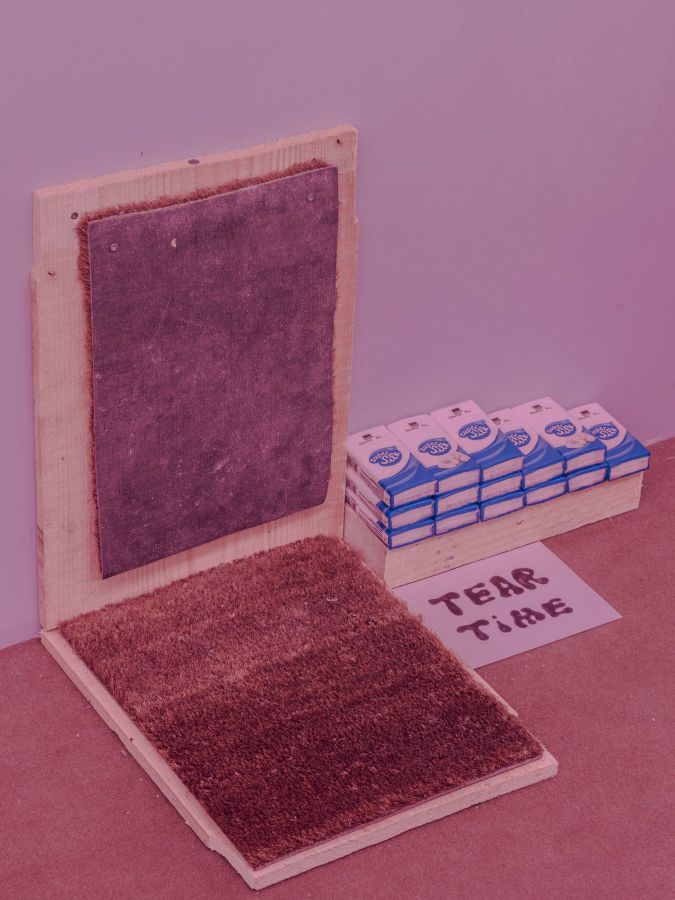

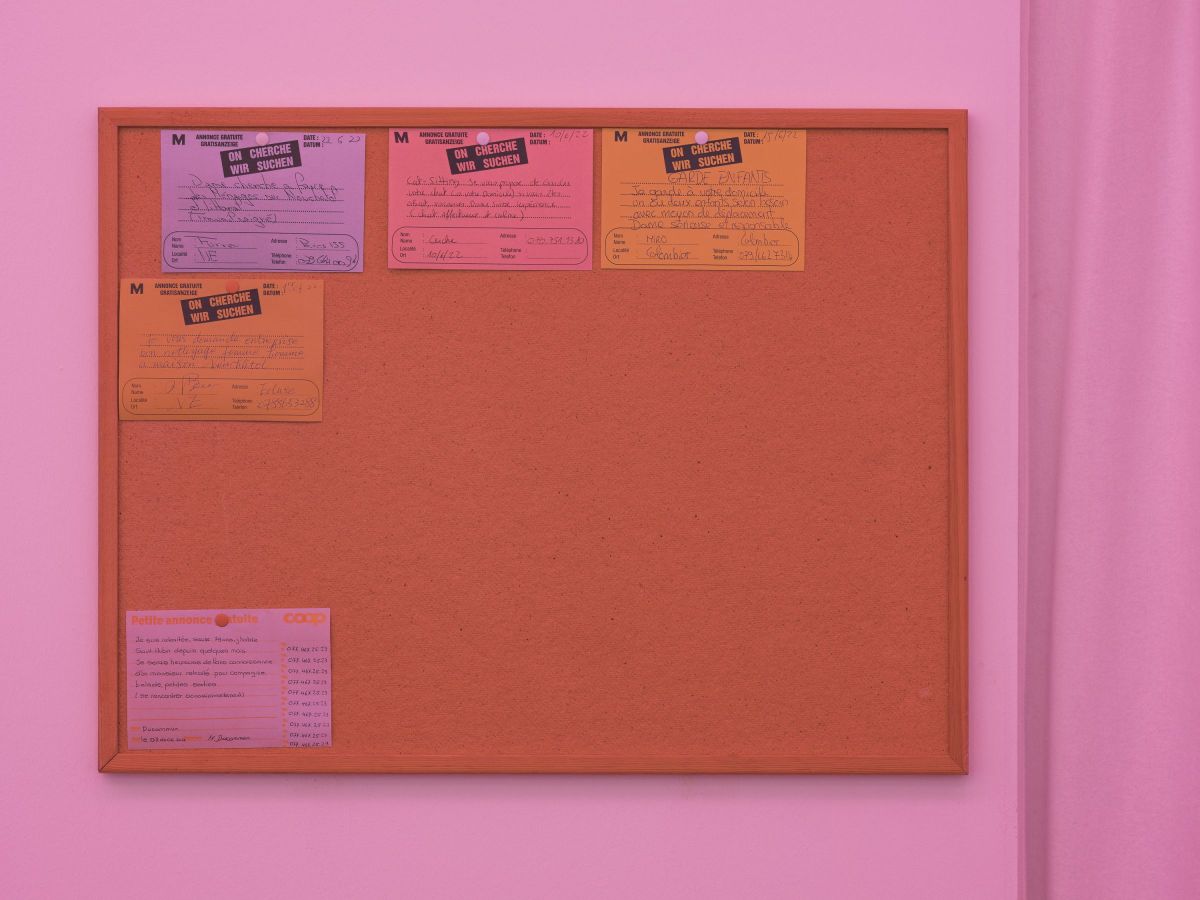

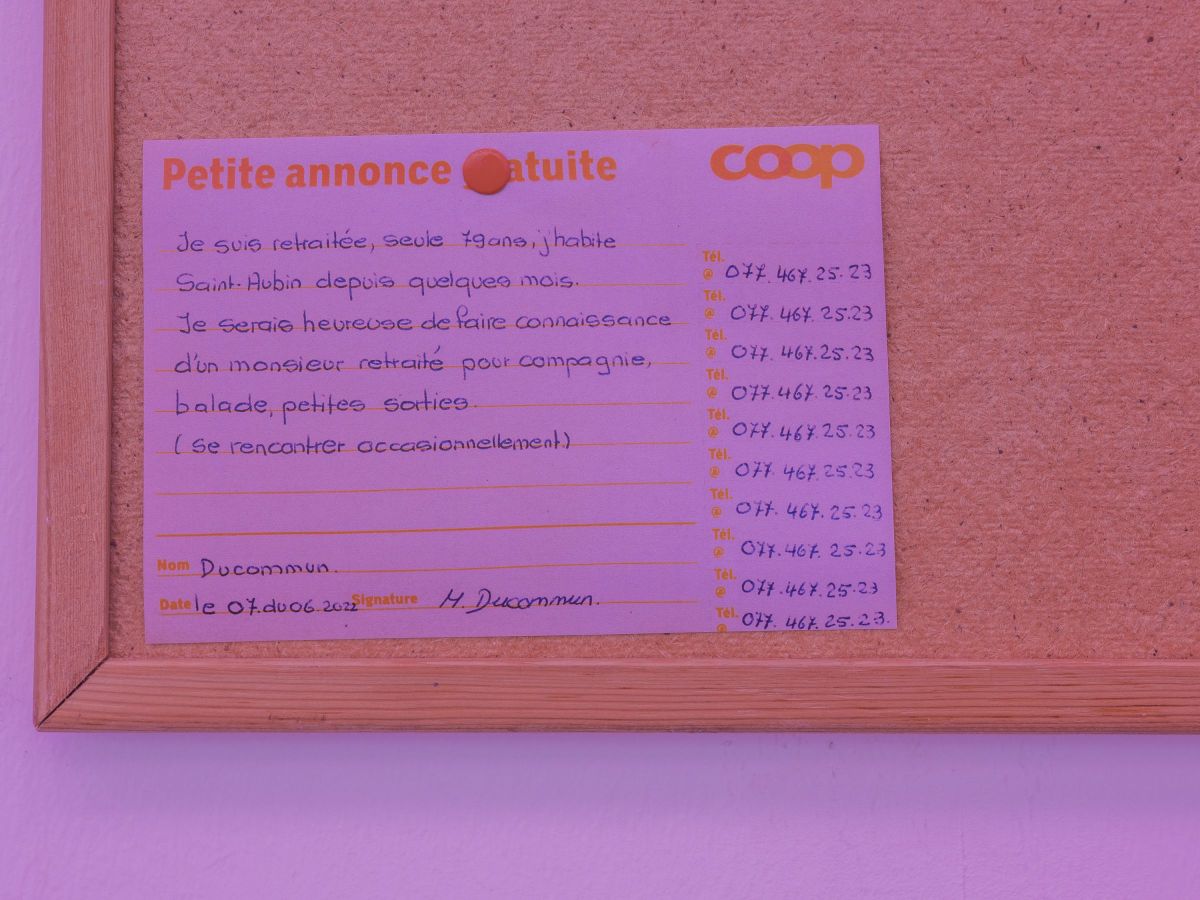

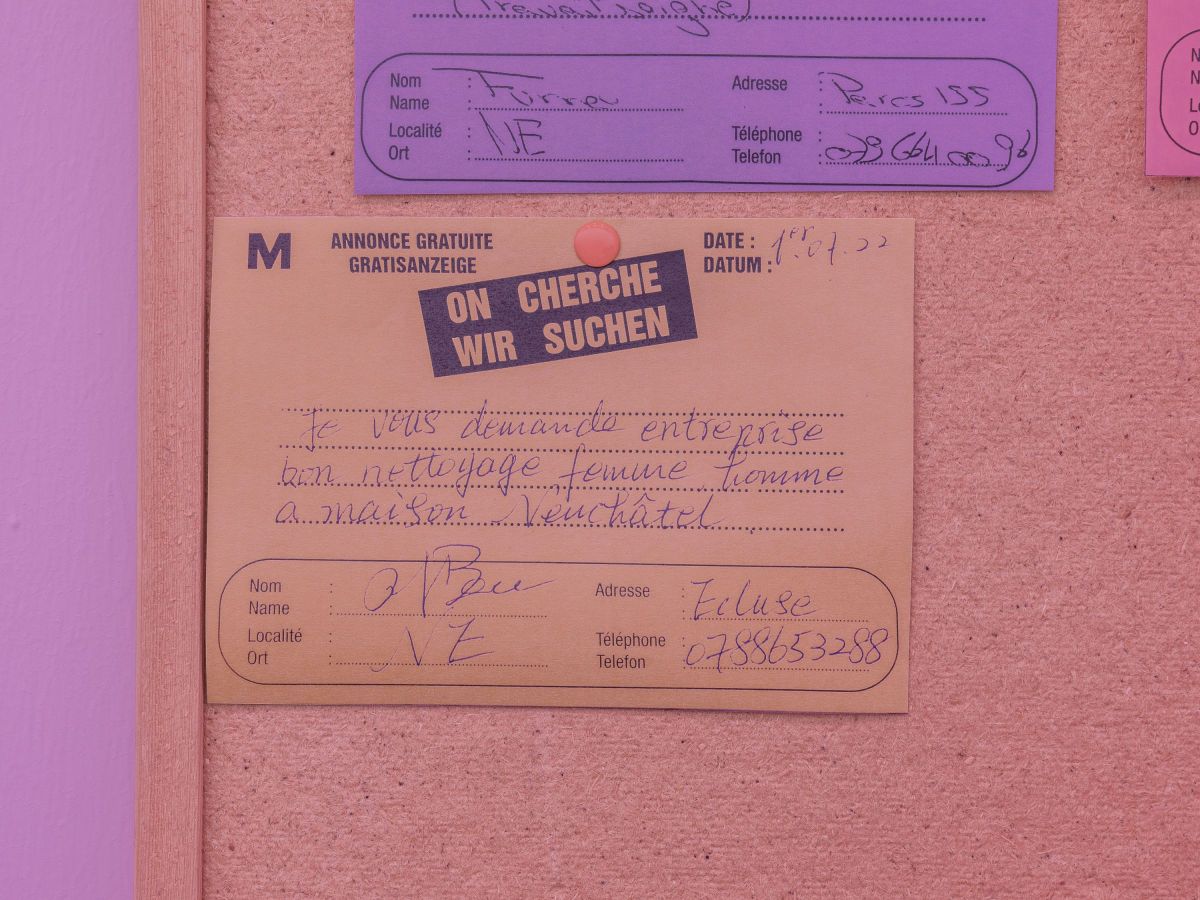

Francesco Finizio’s work is dedicated to imagining ways in which this lack of imagination spirals into a “mise-en-abime”. Finizio’s highly imaginative installation Back in Five Minutes, begins with the viewer entering a setting not so different from an appliance store or repair shop, with a counter, a selection of products and spare parts on display, a shelf and a sign that says “Back in Five Minutes.” On the counter a sign says “Back in Five Minutes.” The customer/viewer gets to look around. The viewing conditions are defined as a bracketed time, before a transaction or query can take place, as the service person is out, and should be back momentarily. Killing time, exploring the store, snooping around (considering shoplifting?) the viewer-turned-customer that is then-customer-turned-viewer can recognise a reception desk that resembles a snack bar, adjacent to which there is a mural display of Happy Harvest dust packets, a wall-mounted planning calendar for reserving time-slots for the machines, Stardust Blends (celebrity dirt bags that seem to be little more than a low-grade unauthorised knockoff of Happy Harvest), paper handkerchief packets promoted as Tear Time, and a message board, boasting ads for cat-sitting, an individual seeking a cleaning lady and another a companion, babysitting, and cleaning personnel looking for work.

As the viewer-turned-customer walks around this entry space, a sound from behind the counter attracts their attention. The whirring hum of fans, a mechanised sound of plastic wheels screeching on the floor. Upon approaching the counter to look behind and inspect where the sound is coming from, the viewer/customer is confronted with a rink of iRobot dust vacuums on the loose.

The physical organisation of the space, with its division into an arena and an observation deck, mirrors these relations of viewer and customer. What are we to make of this?

Finizio writes: “A daring new business venture seems stalled in its tracks / Or is it a social event for lonely low-level employees? / The receptionist has apparently just stepped out and should return shortly, long enough in any case for other entrepreneurial maggots to take root with their own pop-up stores. / But, they’ve gone missing as well. / All that’s left are the machines executing their moves in the rink-cum-playpen-cum-stockyard…and a few humans to watch. / Will their owners return or have they been abandoned? The blissful indifference makes it anyone’s guess. / I’m off to the lake to ponder the ducks.”

Finizio’s poetics allows us to see this world as it is in the most imaginative way possible; it offers a counter-speculation that takes the logic of this world, and runs it down to its inevitable farce. As this world meets its own limits, some moments offer themselves as Finizio-like - during COVID, in makeshift labs, people were paid to hand out stickers, and others to pick your nose – isn’t that a Finizio piece?

In previous works, Finizio has been expanding the viewer/costumer gaze. Some of those that come to mind include his self-portraits with other people’s dogs (“Walking the Dog,” Promenades Plastiques, 1998), which prefigured the Selfie; “Contact Club” (2004-2015), which included a self-portrait of the artist dressed as a remote control, and staged a relation between broadcast images of terror and explosions with the artist’s character’s metabolism, this time depicting the conspiracy theory obsessed person reading signs on the screen and in his own feces; “Promise Park” (2010), in which a deserted pit in a construction site turns into a hellish amusement park; and “How I Went In & Out of Business for Seven Days and Seven Nights” (2008), in which Finizio - along with a set of objects - opened and closed a dozen businesses – from a funeral home and laundromat to peep-show and a mini-golf course. The point here is that the imagined viewer, whoever they might be, is always-already a consumer, and art is not outside of this viewpoint, but has the possibility to entangle it. With his playful makeshift style, Finizio’s clever installations propose the familiar world as it is folded inside-out.

And here iRobot’s autonomous vacuum cleaner, Roomba, makes for the perfect subject. It has become a key example for the shift between reality and its simulation. Spaces and actions are constantly being scanned, not only in order to upgrade them, but more often to apply their behavioral conditioning online. In this way, mapping and surveillance are used for prediction and modeling. Shoshana Zuboff tells of iRobot’s business strategy for the smart home which generates data-based revenue streams, derived from selling floor plans of customers’ homes scraped from the vacuum cleaner’s mapping capabilities. As Zuboff puts it, the relation between reality (aka IRL) and the digital (aka “Online”) is folded inside-out: “Each rendered bit is liberated from its life in the social, no longer inconveniently encumbered by moral reasoning, politics, social norms, rights, values, relationships, feelings, contexts, and situations.” (pp. 210-211)

Back to Finizio’s installation.

Watching kids playing in the park, we are filled with emotions – reflecting on how it used to be when we were young, where we are now, and the distance between the two… While these autonomous vacuum cleaners drive around the floor in patterns that make sense only to them, we are left to wonder: Are they communicating? Working? Playing? Is this work-time or playtime for them? The horror is that it seems like they are having fun! Indeed, this is the worst of all possible worlds…

Joshua Simon